Military Intelligence Service (MIS)

BURMA, May 1, 1944: MIS linguists Technical Sergeants Herbert Miyasaki of Paauilo, Hawaii, left, and Akiji Yoshimura of Colusa, California, right, take a break from jungle fighting in Burma with Brigadier General Frank Merrill, commander of the 5307th Composite Group, Provisional, better known as Merrill’s Marauders. (Photo: U.S. ArmySignal Corps)

More than 6,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry (AJAs) — about half of them from Hawaii — served in the Army’s Military Intelligence Service (MIS) during World War II. Using their knowledge of the enemy’s language and culture, the MIS is credited with saving countless lives and shortening the war immeasurably.

Most MIS Nisei attended the MIS Language School in Minnesota, eventually deploying in small teams to serve at all echelons, from the front lines to the highest headquarters. MIS Nisei served with U.S. divisions in the Pacific and Asia, and with British, Australian, Chinese and other Allied forces.

MIS Nisei served in every combat theatre and campaign against Imperial Japan from the Aleutians and Guadalcanal to China and Okinawa. They interrogated prisoners, translated captured documents, wrote propaganda, made and intercepted radio broadcasts, infiltrated enemy lines, flushed caves and fought as combat infantrymen. Many a MIS Nisei survived a scare when fellow GIs mistook him for the enemy.

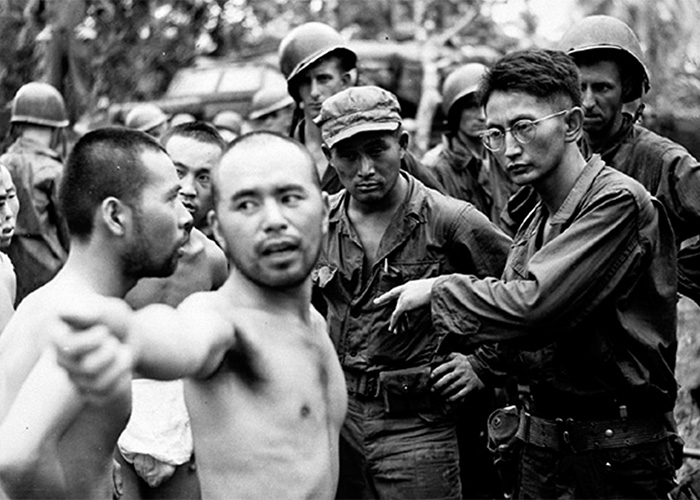

AITAPE, NEW GUINEA, April 22, 1944: Japanese prisoners, left, answer questions from Military Intelligence Service language specialists Harry Fukuhara, right, who volunteered from the Gila River Internment Camp in Arizona, and Shoji Ishii, of San Francisco. (Photo: U.S. Army Signal Corps)

TAROA, Marshall Islands, September 10, 1945: Japanese Rear Admiral Shoichi Kamada, left, surrenders to U.S. Navy Captain H.B. Grow while MIS linguist Donald S. Okubo, of Honolulu, translates; Okubo went alone to Taroa and convinced Kamada to surrender his garrison of 1,000 men. (Photo: U.S. Army Signal Corps)

Notable individual contributions include a Nisei intelligence specialist who discovered the entire Japanese ordnance inventory, proving invaluable in the U.S. bombing campaign and disarmament of Japan. Another MIS Nisei translated a radio intercept that led to the assassination of Japan’s Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. Others translated Japan’s Z plan for the defense of the Philippines.

After the war, the MIS were vital in building bridges between the victorious occupying forces and the defeated Japanese as Japan developed as a modern democracy.

Because much of their work was classified, and done on temporary assignments, their service went largely undocumented and unheralded for years. MIS contributions to victory were finally recognized in 2000 with a Presidential Unit Citation “for outstanding and gallant performance of duty in action against enemies of the United States from May 1, 1942 to September 2, 1945”.

For more information please visit the MIS Veterans Club.

SIMINI, New Guinea, January 2, 1943: From left, Major Hawkins, Phil Ishio and Arthur Ushiro Castle of the 32nd Infantry Division question a prisoner taken in the Buna campaign. (Photo: National Archives)

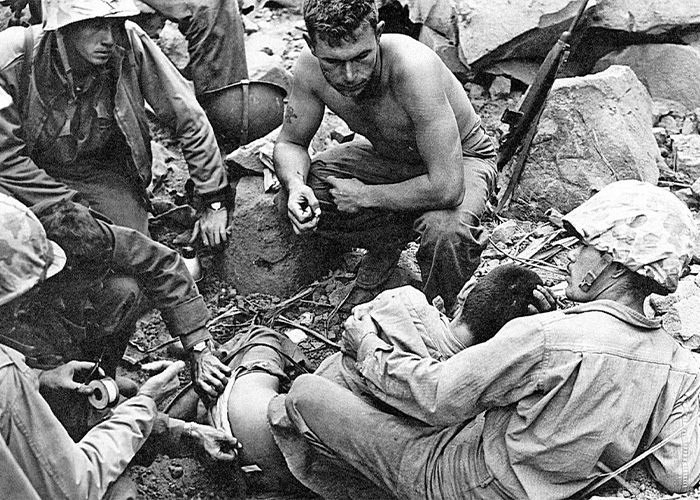

IWO JIMA, March 9, 1945: Tom Miyagi, MIS linguist with the 5th Marine Division, holds a captured Japanese soldier while marines treat the prisoner’s wounds. (Photo: U.S. Marine Corps)

VELLA LAVELLA, Solomon Islands, September 14, 1943: Major J. Alfred Burden and Tateshi Miyasaki, MIS linguists with the 25th Infantry Division, interrogate a captured Japanese sailor. (Photo: National Archives)

OKINAWA, 1945: Warren Higa, left, of Honolulu, questions a prisoner about Japanese positions; Higa and his brother Takejiro were from Hawaii but went to school on Okinawa. (Photo: U.S. Army Signal Corps)