Our Mission

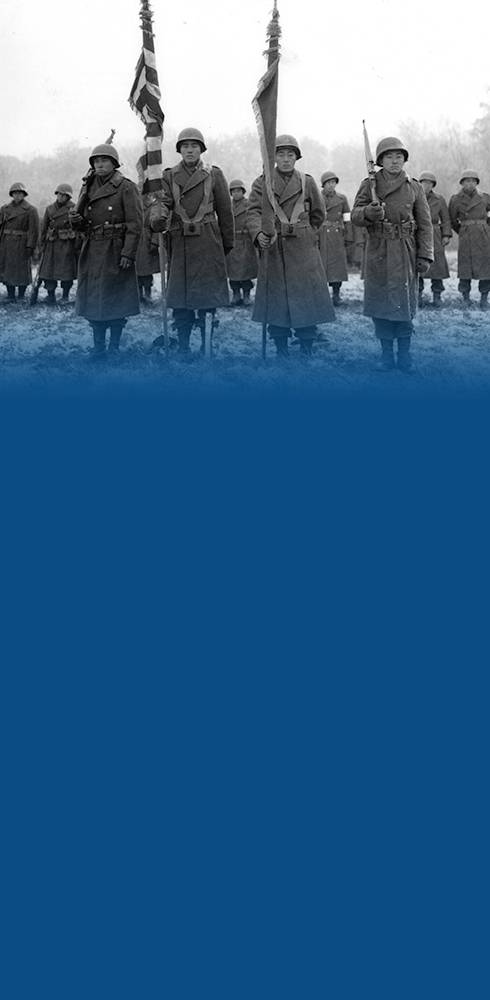

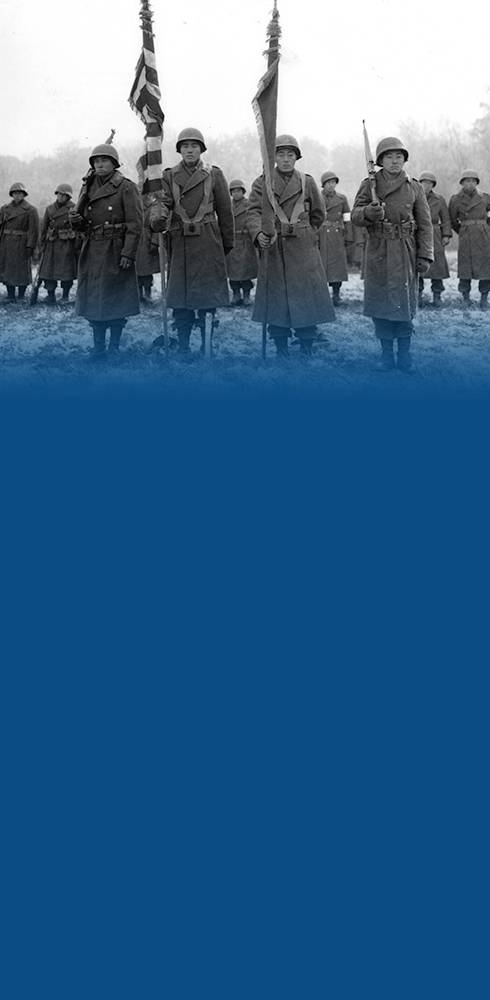

To preserve, perpetuate and share the legacy of Americans of Japanese Ancestry who served in the U.S. Armed Forces in World War II.

Watch vignette of former President Heirakuji speaking about the relevance of the Nisei soldier legacy during NVL’s July 2021 live-streamed educational program.

The Legacy — Why it Still Matters Today

The Nisei soldiers fought the hard fight on the battlefields and on the home front. They instilled the core values taught to them by their Issei parents who immigrated to Hawaii in the late 1800s seeking a better life.

NISEI SOLDIERS: AMERICAN PATRIOTS

Four Hawaii Nisei veterans share their World War II stories.

100th: Takashi Kitaoka

Takeshi Kitaoka awoke on Dec. 7, 1941 to the sounds of an explosion, followed by another. Outside his Kaimuki home, there was chaos in the sky, with strike planes soaring toward Pearl Harbor.

442nd: Robert Kishinami

Robert Kishinami saw planes soaring above his Haleiwa neighborhood and realized it wasn’t a military maneuver with zeroes and tracers. They were real bullets, a declaration of war.

MIS: Herbert Yanamura

Herbert Yanamura was just a carefree high school kid in Kona — the son of a coffee farmer originally from Japan — when the call came for volunteers for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

1399: Richard Okamoto

As part of the 1399 Engineer Construction Battalion, Richard Okamoto’s war experiences are not heroic battle stories. Yet like fellow Nisei, when his country called, he didn’t hesitate to rise up.

Contact Us

We'd love to hear from you!

Request for Newsletters

The NVL issues two newsletters: The NVL News which is a paper and electronic publication providing comprehensive updates about the organization, ongoing projects, and upcoming events. And the Ganbari which contains brief articles and is transmitted only electronically.

If you are interested in receiving future electronic copies of newsletters, send an email to: inquire@nvlchawaii.org